Disc-continued: Shoddy Goods 060

Will there ever be a new physical media format?

Dunno about you, but I’m having way too many moments these days where I realize I’ve lived through the end of something. I’m Jason Toon, and in this Shoddy Goods, the newsletter from Meh about consumer culture, I ask whether the parade of new physical media formats that defined my first few decades has come to an end.

Still waiting for the analog videodisc revival

I was born in 1974. In my earliest memories, record players were everywhere, from my grandma's big living-room console to the rugged suitcase model in my kindergarten class. If you wanted to watch a movie, you saw it in the theater or waited until it was on TV.

You know the story from there. The rise of analog tape swept video and audio cassettes into every home, which were replaced in turn by digital CDs and DVDs. Along the way, a parade of other formats tried and failed to catch on. All of this happened between roughly the late 1970s and the late 1990s. People my age took it as natural that every five or ten years, some new physical recorded medium would come along.

Of course, that's not how it turned out.

"Is the networked era stable?"

All those bygone formats, from vinyl to VHS, have their specialist enthusiasts, their remnants of a once-dominant audience. But now, 15 years after the half-step forward of Blu-ray and almost as long into the unstoppable growth of streaming, the evolution of physical media looks to be over. 4K UHD Blu-rays are a niche medium. The idea of selling music on USB drives pretty much came and went with that one Beatles set. We may have already seen every physical media format that our current civilization will ever produce.

Strip away the sentiment, and all those discs and tapes we got attached to were created as software to help sell hardware. New formats have always been driven by device manufacturers, not the movie studios or record labels, let alone the artists.

Every physical medium was a massive achievement. Scientists and designers had to create the technology. Factories had to manufacture the devices and millions of individual pieces of physical media. Stores had to be convinced to carry them, and media companies had to produce or license content for them. In an age of format-agnostic devices and digital streaming, could that ever make business sense again?

Digital Audio Tape: all the hassle of tape, at CD prices!

"Normally, if a journalist reached out to me and said, 'hey, can you predict the future?', I'll always say, 'no, I can't,'" says Jason Mittell, Professor of Film and Media Culture at Middlebury College. He's written several books about television genres and storytelling, and he's been thinking about the "post-disc world" since at least 2009.

"But I guess the question that to me seems really most vital to this is, is the networked era stable?," he says. "We think it is. But we've thought a lot of things are stable that turned out not to be, right? So the big question is, is there a moment in which the system that underlies the idea that I can buy a temporary license to watch anything - not anything, but many things - is going to hit enough of a snag to make it like, oh, the physical media have value again?

"Probably not, unless we're talking, like, the Mad Max world. But my guess is if we're in that, being able to watch The Matrix is not my top priority. You know, you need electricity today for any of these things."

Yikes. If it would take a global technological collapse just to consummate the vinyl comeback, it's not looking good for the Herculean industrial effort that would be required for any new format to take hold.

Mittell’s pessimism about the future of physical media is hard-won, as he's watched the essential source material for his life's work almost evaporate. "One of the things that my department does is purchase physical media for our university library," he says. "Ten years ago, we were purchasing up a storm. And now there are just fewer and fewer titles that are available in physical media. We still do it because we know that there'll be even fewer next year.

"A lot of my research is on American television, and television is much, much harder to find on physical media now than it was. There was that golden moment from the late '90s, early 2000s, to like 2015, where everything was put out on DVD or Blu-ray. We thought, oh, well, this is going to be the way it always is. And now it's not."

"The five-inch disc just works"

Andreas Babiolakis is a lifelong cinema superfan who reckons he has watched his favorite films (Stanley Donen's Charade, David Lynch's Mulholland Drive, and Darren Aronofsky's Black Swan) fifty times each on Blu-ray. He's also a film critic who writes at Films Fatale and has a Master’s degree in Film and Photography Preservation and Collections Management. To him, the viewer-streamer relationship is a case of easy come, easy go. The flipside of convenience is precarity.

"In the same way that I could watch William Friedkin's The French Connection at a whim via streaming, The French Connection could be silently censored without Friedkin's involvement," he says.

The most coveted flash drive this side of a Jason Bourne movie

"Say that all copies of Citizen Kane ceased to exist anymore because of some freak, spontaneous-combustion accident. It is only available on streaming, for whatever reason. If a greedy child of a hedge fund billionaire -- who happens to be in charge of Citizen Kane now -- chooses to pull it from streaming just because he feels like it, that film is effectively lost."

That has happened already with streaming-only releases. It's easier to legally watch a random B-movie from 1987 than many recent Disney productions, for instance, because you can probably find an old VHS copy of the former.

"I saw some of John Waters' early shorts at the Academy Museum in L.A.," Babiolakis says, "and I am so fortunate that I did because they essentially do not exist outside of this institution for anyone to watch; if anything happened to them there, they're gone. Forever. This is John Waters we're talking about."

Like Mittell, he's hesitant to predict the future evolution, or not, of physical media. But if there ever is a new format, his money is on higher-resolution discs, like 8k - "The five-inch disc truly is a standard, isn't it? It kind of just works" - with substantial archival packaging, to cater to the audience that's still willing to pay for physical discs.

"I honestly feel like consumers love what Criterion, Arrow, Kino, Vinegar Syndrome, and other companies offer with their physical media," Babiolakis says, citing the "thought-out design along with amazing supplementary features" offered by these connoisseur labels, producing an archival item that feels like it's worth owning. "It also costs more to purchase these kinds of releases, and yet I much prefer them over shoddy, cheap releases."

Nothing lasts forever

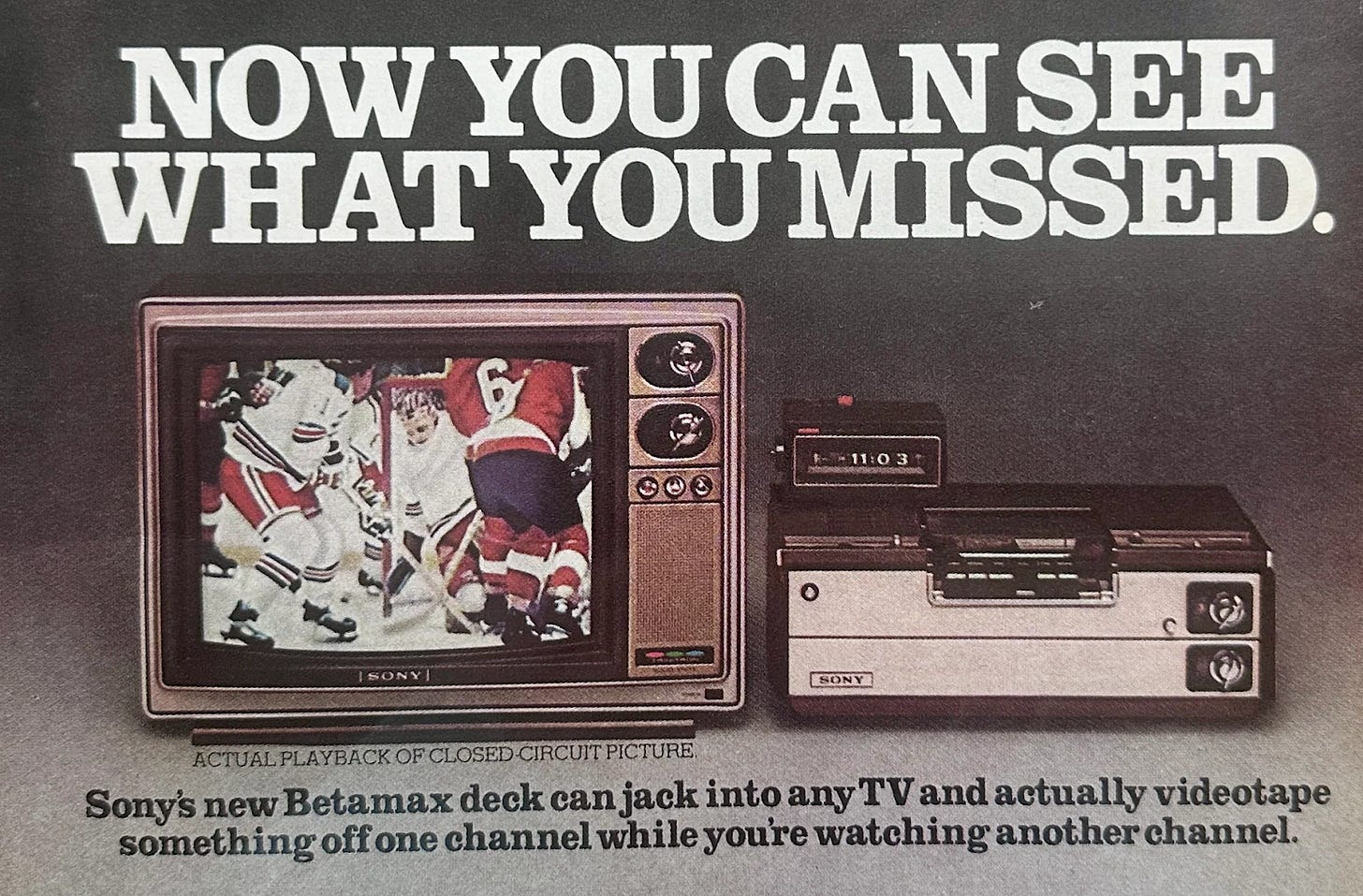

Betamax is forever

Indulging my request to speculate, Mittell also looks at the question of what physical media can give us that streaming can't, and points to two currently thriving examples. One is printed books, which despite predictions, are still selling well in the face of audiobooks and ebooks. The other is a bit more surprising: board games.

"You can play most board games online," he says, "and yet people are still buying them, right? And I think that that speaks to the way in which a medium that creates social, physical, interactive engagement is going to be the thing that you can't quite replace."

Mitell isn't sure how that might translate to a new medium, though: "There have been a bunch of experiments of trying to come up with interactive cinema and they all suck."

It's strange and, I can't help it, a little sad to think that the development of physical recorded media was a hundred-year blip, an anomaly between two more ephemeral ages: the lost pre-history of live performance and the network-dependent future of ones and zeroes.

Both of my interviewees remind me, though, that permanence is relative. "We do have to remember that every physical medium has a shelf date," Mitell says. "They do degrade, right? I have piles of VHS tapes that I'm assuming if I had a way to watch them, they wouldn't work."

"Film was a highly ephemeral medium at first," Babiolakis says. "Silent films were being churned as quickly as possible… It was the initial ephemeral quality of film that has rendered so many early films lost; of course, then came the infamous nitrate fires, films being melted to use for other resources during World War II, et cetera. Seeing as there is such a focus [now] on trying to keep what we presently have, I'd like to think that this media we cherish will remain."

Chances are, if it does, whatever physical form it takes will look familiar.

I actually have that Beatles USB apple, though I just looked it up and it seems available for about what I paid for it 15 years ago. Do you remember your first purchases on the different physical formats? I remember getting my first cassette tape (I believe it was Asia), and my first CD (the Stand By Me soundtrack). I remember having a couple Men At Work albums on vinyl, but I’m guessing I just got those from my brother. Remember what music and movies did you first get on each media format? Let’s hear about ‘em in this week’s Shoddy Goods chat.

—Dave (and the rest of Meh)

These old Shoddy Goods stories are available wherever fine 8-tracks, Laserdiscs, and DATs are sold: