Earlier every year?: Shoddy Goods 021

Looking for evidence of Christmas creep

I'm Jason Toon, and like my heroes from Johnny Cash to Pee-Wee Herman, I'm putting on my own Christmas special! Only instead of a variety show, it's a month of hall-decked, figgy-puddinged holiday editions of Shoddy Goods, the newsletter from Meh about the stuff people make, buy, and sell. So, not like those other ones at all, I guess. Anyway, this week, I look at one of the most cherished cliches of the seasonal cynic to see if there's any truth in it…

"Every year merchants, whose ears perk at the jingle of coins when most people aren't even thinking about jingle bells yet, have been bent on making the Christmas season come earlier," complains one commenter.

"Save a little Christmas spirit for Christmas Day," agrees another. "Promoting Christmas right after Halloween has given almost two months of seeing Christmas everywhere. When I was a kid, Christmas was at Christmas time."

“Christmas doesn’t only seem to come earlier every year,” says a saleslady in Los Angeles. “It actually does."

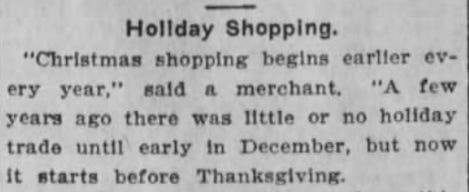

"Christmas shopping begins earlier every year," confirms a merchant.

Yes, everyone agrees: the Christmas retail season keeps getting pushed earlier and earlier into the year. Problem is, the first quote is 40 years old, from a 1984 newspaper editorial. The second is even older, published in 1974. Our LA "saleslady" was quoted in Time magazine in 1966. And the last comes from all the way back in 1904, from this piece in the Birmingham Post-Herald on November 8:

You might be wondering when exactly this vanished era was, when Christmas sales started at the "right" time. So was I.

Taking potshots at Santa

Music was objectively better when I was a teenager. Young people these days are lazier, more pampered, and less respectful. And Christmas keeps getting earlier every year.

The first two of those tropes have been mocked and discredited. Every generation has to endure them, and then hurls them at later generations in turn. But is there any reason to believe the third one is any more valid?

I wanted to find out. Not if people feel like Christmas starts earlier than when they were young - obviously they always do - but what the evidence shows.

I'm not the first to try. A piece in The Guardian purports that 'Christmas creep is real', citing three data points limited to the UK: when the first Christmas record enters the British pop charts, what date the supermarket chains start selling certain Christmas goodies, and when local outdoor Christmas markets open. But their data doesn't go back that far: to 1980 for the songs, 2020 for the treats, and 2010 for the markets. When people say "Christmas used to happen at Christmastime", they're usually not talking about back in the year 2020.

So it's a profit deal… the editors of the Boca Raton News bust the racket wide open, November 21, 1984.

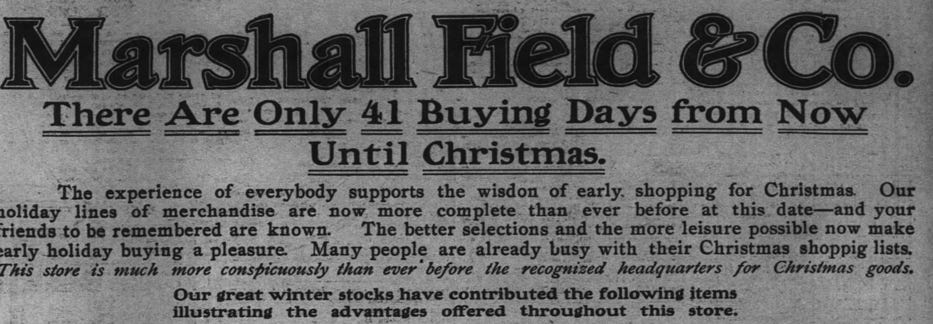

Arguing the other case, writers Paul Collins in Slate and Bill Black in Contingent Magazine are unequivocal. "Actually it's been starting in early autumn since the Victorian era," as Collins put it. They dug into newspaper archives to find copious examples of both Christmas advertising in September and October, and of people using the "earlier every year" trope.

Both unearthed some gems along the lines of the quotes I found at the start of this article. “Some of us will become so tired of seeing Santa hanging around weeks on end we’ll be taking pot shots at him,” Black quotes a Cincinnati Enquirer editorial from 1944. If you're interested in this subject at all, both of those pieces are fun reading (after you finish this one, of course).

So yeah, there's always been some Christmas hucksterism before Thanksgiving, and some people saying it didn't used to be like this. But that doesn't really answer the question about whether there's been a general trend over the decades where "Christmas starts earlier every year." Can we turn those anecdotes into data?

The good old days weren't 1944, according to this November 9 ad from the Omaha Papillon-Times.

Run run (the numbers), Rudolph

I'm no scientist, and what follows isn't exactly science. But I do have a newsletter to fill, so I'll take a shot at it.

Collins and Black were on the right track, I thought. Newspapers were as central to people's lives during the 20th century as the Internet is today, with the added advantage of being centrally archived and searchable in a way online content will never be. They're the closest thing to a time machine we have. I may not be able to ask people in the past what's on their minds, but I can rely on thousands of editors and advertisers whose jobs depended on knowing their audience.

So I went to my beloved Newspapers.com and started searching - not just to dig up more counterexamples, fun as that is, but to add up search result volumes for "Christmas", week-by-week, from October 24 right up to Christmas.

I quickly realized, whoa, the past has a lot of different dates. Rather than look at every year in the Newspapers.com database, going back to the 1700s, which might take me the rest of my natural life, I'd look at every ten years from 1904-2004. That gives us snapshots through a nice, round century. It spans the dawn of modern Christmas as we know it through the early social media age. And it should cover the memories of everyone alive today, their parents, and most of their parents' parents.

Also, just comparing years' raw totals to each other was too noisy, too dependent on how many newspapers were published and archived, and thus on factors like depression and war. So I decided I'd set the number of results for the week leading up to Christmas to 1, and figure each week as a percentage of that. Basically, this would show us how steep - or not - the ramp-up to Christmas was for each year.

One more thing: I only included results for U.S. newspapers. Our unique late-November Thanksgiving holiday gives the American season a certain shape, and most of you are Americans anyway.

So here's what I found, the arc of the Christmas season, every ten years from 1904 to 2004:

See that blue line at the bottom? That's 1904. And then the little cluster of lines above it is the next three decades: 1914, 1924, and 1934. Every year after that is then clustered together right around the 25 percent mark for that first week.

So: someone in 1914 would have had cause to say Christmas seemed to be starting earlier. Same for someone in 1944.

But since then? The annual progression toward Christmas has been remarkably stable. Newspaper chatter crosses the 50 percent mark in mid-November, really jumps in late November, and slowly climbs or plateaus from early December until Christmas.

Bottom line: Christmas does not seem to have been "getting earlier every year" since at least World War II.

But what about the last 20 years?

On the one hand, I don't know. Since the early 2000s, newspapers have become less reliable barometers of the public mind. There are fewer of them, they're smaller in both circulation and page count, they're less influential, and far fewer of them are centralized and searchable.

On the other hand, is there a good reason to believe it might have changed? "It just seems like it" isn't a good reason. We've just seen how it has "seemed like" Christmas was perpetually getting earlier when it wasn't. Google Trends doesn't measure the same thing as my little newspaper survey, but if anything, "Christmas" search volume shows an even later "start" to the season.

OK, there's the sprawl of Black Friday into a November-long event. But have you noticed how rarely you see any Christmas iconography associated with it anymore? Or even gifting imagery? It's become its own weird artificial retail occasion, a reason to splurge on yourself as much as a Christmas thing.

In the absence of evidence to the contrary, I'm more inclined to think that the "Christmas gets earlier every year" trope is about as true as it has been for the last 80 years: not really at all.

So why does it still carry the force of unquestioned truth for so many people? Is it just another nostalgic belief that everything in the past was more pure and honest? Is it our tendency to give undue weight to things that violate our expectations? One Santa Claus in September is worth a thousand Santas in December, in terms of memorability.

The truth is, when there's money to be made, there will always be somebody trying to get the jump on grabbing it first. But the very persistence of the complaint undermines its own case. Clearly, most of us dislike the idea of Christmas creep so much, we're hypervigilant, ever ready to loudly damn any sign of it. Retailers hear this and tread lightly. Perpetuating the myth of too-early Christmas might be the best way to keep it a myth.

Retailers have their own schedule for when to pitch us on the holidays, but, if you celebrate Christmas, what’s your rule for when it’s ok for the decorations to go up?

Personally, we go pretty early - indoors, often the week before Thanksgiving. But I try to hold back a bit longer for the outside decorations. Honestly, though, once it starts getting dark early, all bets are off for anything I can do to get some extra light and festivity going. And you don’t want to know how late we leave everything up. Join us in this week’s Shoddy Goods chat to discuss holiday timing and when exactly “the good old days” were.

—Dave (and the rest of Meh)

This season, give yourself the gift of professional-grade infotainment with these past stories from Shoddy Goods, because they're free and you're worth it: