Lindmania!: Shoddy Goods 049

The original queen of music fan merch

I'm Jason Toon and I probably spent about 50% of my time between the ages of 15 and 25 in band t-shirts. This issue of Shoddy Goods, the newsletter from Meh about consumer culture, takes us back to the dawn of music fandom as we know it - even before recorded music itself.

The pre-Madonna prima donna

"Oh, you like Nirvana? Name three of their songs." We all know the stale trope of the fan wearing a t-shirt festooned with the logo of a band that some know-it-all has assumed they're not sufficiently dedicated to. Probably bought it at Target, scoff the gatekeepers (who skew male) at those they accuse of poseurdom (who always seem to skew female). Somewhere in that tiresome stance is a notion of authenticity lost, that such merchandising is a recent perversion, that it used to be about the music.

But many of the fans who snapped up the earliest music-star memorabilia couldn't possibly have heard that star's music. Because sound recording hadn't been invented yet, and she only toured the U.S. once, from 1850-1852, playing about 150 shows for steep admission prices. Maybe 1% of the U.S. population could have ever heard her sing a note: Taylor Swift-scale proportions for a live tour, but those were the only people in America who heard her.

And yet the mystique of Jenny Lind, the Swedish Nightingale, was enough to spawn a dizzying array of merchandise, both authorized and not, some of which still bears her name today.

Live! One Nightingale only

From cents to scents: a Jenny Lind coin purse and Jenny Lind perfume

By 1849, Phineas Taylor Barnum was the unquestioned king of the sideshow. At his American Museum in New York, and on tours around the country, he peddled crowd-pulling hoaxes like the "FeeJee mermaid" (a taxidermied monkey with a fish's tail) and "General Tom Thumb" (a child actor with dwarfism). But as his forties loomed, P.T. Barnum began to crave the respectability befitting a prosperous family man.

He was touring Tom Thumb around Europe when he found his vehicle to reach a more genteel audience: Jenny Lind. The Swedish opera singer was so popular and had earned so much money in Europe, she was preparing to retire at just 29. Without hearing her sing, Barnum persuaded her to tour America for the then-unheard-of fee of $1,000 per night (about $40,000 today). Lind agreed only because she wanted the money for her charity work setting up schools for the poor in Sweden.

So the gutter huckster and the opera philanthropist went into business together. At a time when industrialization was transforming the country, bringing smoke and noise and unfamiliar accents to towns and cities, Barnum promoted Lind as a sweetly serene flower of demure womanhood with planted stories like this, from the New York Home Journal on March 23, 1850: "To a mind eminently sensitive, a heart still free from world stains, and the uninterrupted habit of a daily observance of her religious duties, may be justly ascribed the manifestation of Jenny’s humility, tender-heartedness, and sensibility."

She was big. Paper dolls big. Photo albums big. Cast-iron trivet big.

Barnum's full-court press worked like the dickens. Tickets for her American shows started at $7 (about $280 today), but when Barnum saw the demand, he auctioned off tickets for up to $200 each (about $8,000 today). Old P.T. could teach Ticketmaster a thing or two about shameless profiteering.

Lindmania wasn't just a phenomenon of the wealthy. Rowdy mobs gathered outside theaters from Boston to New Orleans, straining to glimpse the Swedish Nightingale, or hear her through open windows. The notoriously rowdy volunteer fire companies of the time - essentially gangs of street brawlers - were especially big fans. LeRoy Ashby's great book With Amusement for All tells of one Appalachian teenager who walked 60 miles to see Lind in Wheeling, West Virginia, fixing clocks along the way to earn the money for his ticket.

Literally from the moment Lind's ship docked in New York, Barnum peddled a full range of official merchandise. Forget t-shirts: we're talking lamps, pianos, portraits, sheet music, perfume… and whatever class of goods Barnum didn't think of, other hustlers did. "Intellectual property" wasn't much of a concept in 1850. Jenny Lind's name was gold, and the profiteers of this cut-throat age didn't hesitate to cash in on it. Everywhere she went - and she went a lot of places during her 18-month sojourn through that old, weird America - local vendors invoked Jenny Lind to cast an aura of class and quality over their wares.

Put a Swedish Nightingale on it

After Barnum promoted 93 extremely lucrative shows and Lind demanded at least one renegotiation of her contract, the two parted amicably over Lind's unease at Barnum's relentless commercialism. She continued the tour herself, marrying her piano player Otto Goldschmidt along the way and retiring with him to Europe. (Despite what the movie The Greatest Showman depicts, there's no hint that she and Barnum ever had a romantic relationship.) The $350,000 she earned on the tour ($12 million today) did indeed go to endow her charities. Lind is believed to have made exactly one recording, a primitive Edison cylinder, long after her prime and shortly before her death. It is now lost.

From soup to spuds

The impact of Lind's fame seems unbelievable to us today. In an age with no electronic mass media, the only way for most people to experience Lindmania was by looking at pictures of her (she wasn't especially known as a beauty and joked about her "potato" nose), reading accounts of her concerts (about as satisfying as dancing about architecture), or perhaps singing along to the sheet music of her repertoire (none of which was written by or unique to her).

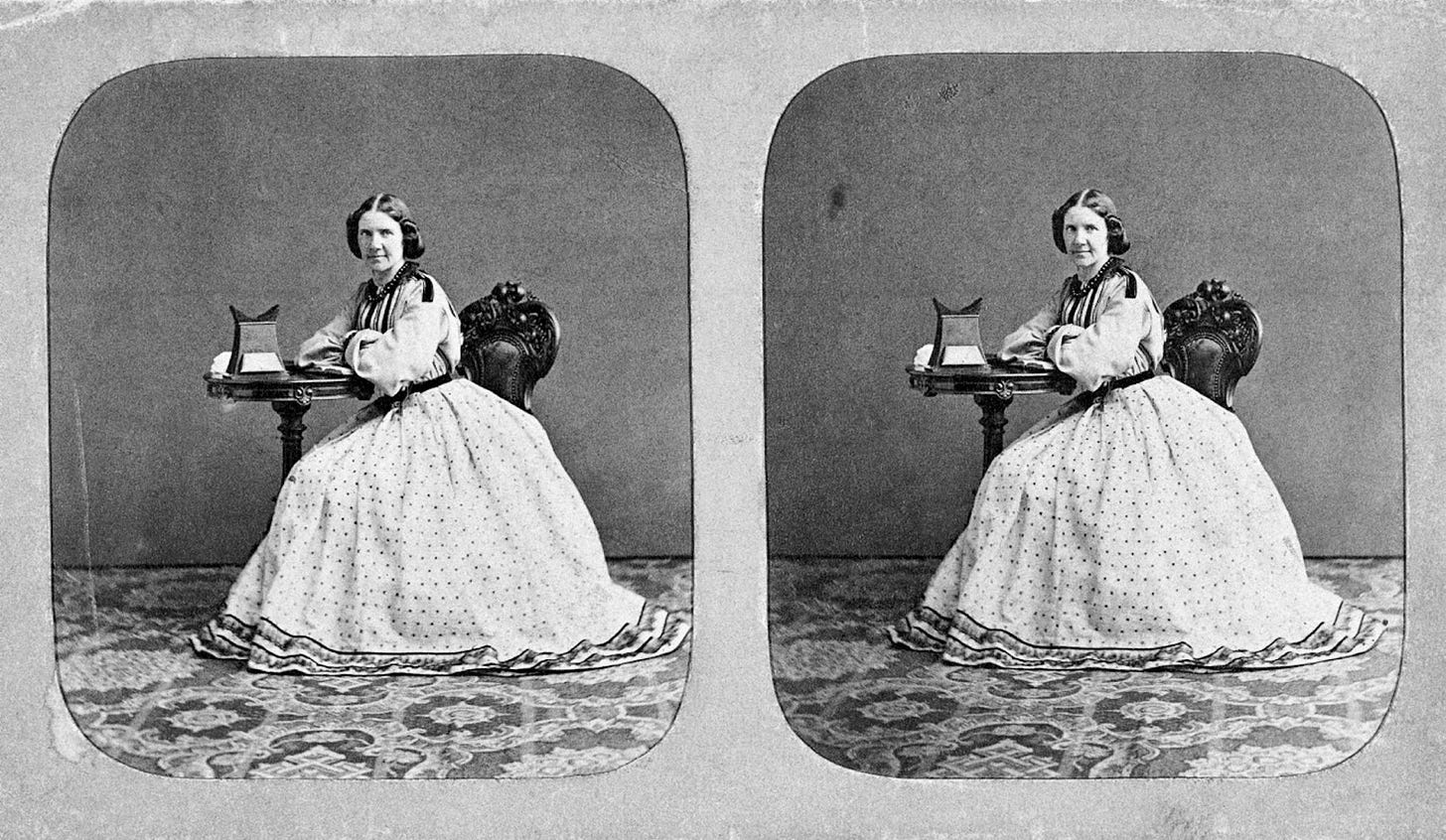

If you focus just right, it's like she's here

And yet, not only did her fame far exceed her geographic reach, it extended well beyond the end of her life in 1887. She's given her name to varieties of potato and canteloupe, to cities in California and Arkansas, to streets and geographic features across the country. In James Joyce's Ulysses, the protagonist Leopold Bloom rhapsodizes about a "creamy dreamy" mashed-rutabaga dish called Jenny Lind soup.

The name lives on attached particularly to a couple of kinds of products. Jenny Lind dolls still have a loyal following of collectors. But most people will have heard her name in reference to Jenny Lind furniture, featuring woodle spindles crafted to resemble spools. Her only connection to the style is that she allegedly slept in a spool-spindle bed on her tour. But in the heat of Lindmania, that was enough to brand them "Jenny Lind beds".

Oh, you sleep in a Jenny Lind bed? Name three of her songs

Again, such fame seems disproportionate to the number of people who could've been moved by her music. Which is one more way P.T. Barnum was way ahead of his time. He and Lind pioneered a model of musical notoriety in which the music itself mingles with the performer's style and charisma, and the audience's imagination, and significant doses of managerial savvy and media buzz. Regardless of whether she sang pop music, Jenny Lind was a pop star.

What band shirts and other merch have you bought over the years? I think my first band shirt was from The Monkees reunion tour in '86 or '87. Kind of wish I still had that one. Let’s hear about yours in this week’s Shoddy Goods chat.

—Dave (and the rest of Meh)

More stuff about music for people who love music stuff: