Halloween's Least Wanted: Shoddy Goods 068

The mystery of peanut butter kisses: an investigation

I’ll apologize in advance to anyone who loves the candy that I lay into in this Shoddy Goods, the newsletter from Meh about consumer culture. I’m Jason Toon and I don’t want to harsh anybody’s mellow. But seriously, peanut butter kiss lovers, you deserve so much better.

Every November of my childhood, after the Starbursts faded, the Kit Kats slunk away, and the Jolly Ranchers rode off into the sunset, one kind of candy was left. Blandly unappetizing in both its pale tan hue and even paler taste, somehow both rock-hard and tenaciously sticky, this stuff was like taffy drained of all color, flavor, and will to live. It’s the candy that a sadistic Victorian headmistress would serve the urchins in her care, more punishment than treat.

This resinous confection was packaged under various guises that all seemed more at home in a candy museum than a plastic jack o’lantern: Bit-O-Honey, Mary Janes, and most depressing of all, wrapped anonymously in either black or orange wax paper. In this case, the molasses blob has a little pocket of peanut butter inside, which only adds to the impression that they just scraped up everything that dripped on the floor of the candy factory and melted it down into a new candy. Of course, I still ate every single one, every year. Candy is candy.

Cyber-wags have been cracking wise about these gobs of heartbreak as long as there’s been an Internet. One meme says they “taste like a mixture of molasses and child abuse. Their manufacturer is so ashamed of them that nobody is even sure what they’re called.”

I didn’t myself until I started writing this story. Turns out they’re called peanut butter kisses. And I wanted to find out who inflicted them on us.

TRIGGER WARNING

Mary Jane was innocent

I thought my investigation was over as soon as it had begun when I immediately found this post on the Food Historian blog by Sarah Wassberg Johnson, a (you guessed it) food historian. She calls them “Mary Jane Peanut Butter Kisses” and describes them as a spin-off of the aforementioned candy by that name. “At some point,” she writes, “the small rectangular candies wrapped in an iconic yellow and red printed paper were succeeded by the ‘kisses’ - the rough rounds wrapped in black or orange waxed paper.”

With all due respect to Johnson, that story doesn’t quite add up. For one thing, the original Mary Janes never went away. For another, why would the Mary Janes manufacturer brand these candies but continue packaging the individual pieces in unmarked wrappers? Turns out, they wouldn’t. Mary Janes brand peanut butter kisses do have Mary Janes logos on each individual wrapper.

A 2006 review of Mary Janes Peanut Butter Kisses confirmed that these were but one variety of the oft-maligned sweetmeat.”I don’t know if I’ve ever had ‘name brand’ peanut butter kisses before,” the review says. “These are the first I’ve ever seen that have anything on the black & orange wax wrappers.” (Incidentally, the reviewer rated them 8 out of 10, with several supportive comments among the outraged ones, proving that somebody must like these things.)

Looked like this rap wasn’t going to stick to Mary Jane. To solve this one, I’d have to hit the streets - meaning, in my case, online archives.

See you in the funny papers

Don’t feed these to babies. Or grannies. Or anybody else. Pittsburgh, 1946

For those of us interested in the commercial history of the 20th century, newspaper advertising is our secret weapon. Newspaper ads reveal peanut butter kisses in myriad other guises. Mass-produced brands were the top layer of sediment, like this 1976 supermarket ad for Brach’s, and local brands like Chicago’s PSC in this 1960 ad. A little deeper, and I found ads for department-store candy counters touting their in-house PBKs, like Sears from 1948 and Rosenbaum’s from 1946.

“Everyone from Granny down to Baby has a sweet treat in store,” the latter ad copy said. “Chewy, tasty peanut butter kisses are palate-pleasers anytime.” Not a mention of Mary Jane in all this insanity. I think we can safely rule her out as a suspect. Just how deep did this thing go?

I pushed back through the decades, back to even before Mary Janes were created. I found countless ads like this one from 1909 for a Maine candy store. A photo from a Buffalo fair that same year, showing a tent offering “Wuest’s Peanut Butter Kisses.” A 1902 ad for a Washington DC department store promoting “PEANUT BUTTER KISSES, MADE FROM PRIME MOLASSES AND PEANUT BUTTER.”

So contrary to the Food Historian blog post (which, of course, Google AI is now repeating as the truth), peanut butter kisses predate Mary Janes entirely. I was starting to think nobody was to blame for this crime. Or maybe… we all were.

Kiss machine

Other sources pointed to the ubiquity of peanut butter kisses as a standard, widespread, generic offering of early 20th-century candy stores. The novel The Jaybird by MacKinlay Cantor, published in 1932 but set around 1916, has small-town kids drooling over a dime-store display of peanut butter kisses “pouring out of a wooden barrel.”

Recipes for peanut butter kisses appear in numerous pre-WWII cookbooks and home magazines, like the one in a 1930 candy cookbook for home use, Candy Recipes by R.R. Stewart, where the peanut butter is partially mixed into the molasses but left “in streaks through the candy.”

Looking for a kiss, Washington DC, 1902

A 1912 manual aimed at professional confectioners, The Twentieth Century Candy Teacher by Charles Apell, settles it once and for all. With ingredients including 20 pounds of glucose, 15 pounds of sugar, and 5 pounds of condensed milk, its recipe for peanut butter kisses is just the right size for the candy store who probably made most of their own candies on the premises.

Did you know “kisses” were a generic candy type long before Hershey’s Kisses came along? I didn’t, but many of these recipes sit alongside others for the likes of black walnut kisses and caramel coconut kisses. Apell’s unexplained reference to a “kiss machine” got me curious, leading to this footage of a vintage kiss machine in action, more widely (but less sexily) known now as a taffy wrapping machine.

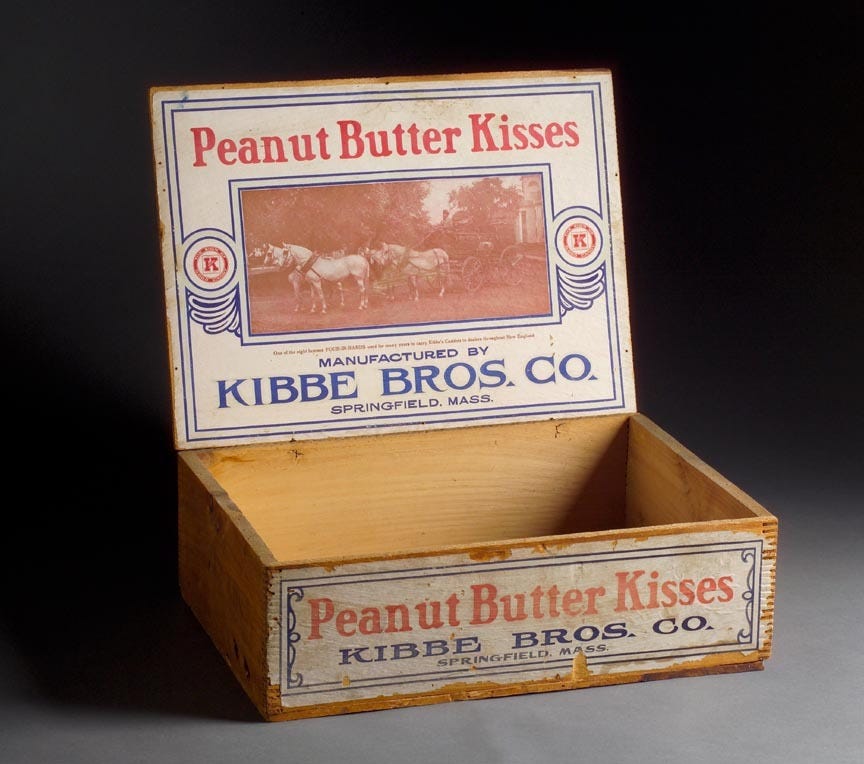

Anyway, just as nobody owns the concept of taffy, nobody owned kisses, peanut butter ones included. A 1923 trademark filing by the Kibbe Brothers Company registered their distinctive wrapper for peanut butter kisses, not the candy itself.

To think, this box could’ve been holding something more wholesome, like cigars

Grassroots? More like grossroots

So there it is. Peanut butter kisses are nobody’s fault. They’re a vernacular candy. A grassroots phenomenon. A treat that spread organically, not because of the brute marketing muscle of some big multinational conglomerate. It was originally a locally produced, hand-made product with a short list of easily pronounceable ingredients.

What’s more, the flavor and color that kids like me found bland was characteristic of a time when American food was less artificially jazzed with dyes and chemical flavorings. Our great-grandparents liked peanut butter kisses because their taste buds hadn’t been blown out by easy access to hyper-sweetened junk food.

All of which makes me feel a little bad for hating peanut butter kisses so much. But not enough to eat them.

Line drawings don’t do them justice. Chicago 1960 and Manhattan, Kansas 1976

Everyone knew that one house that gave out full-sized candy bars, but there was also that weird house that gave out random loose change. As a kid I always loved the mini-boxes of Nerds since they’d last longer, so I could draw out the time I was rotting my teeth before having to go back to ‘real’ food. Let’s hear what your favorites and most hated treats were in this week’s Shoddy Goods chat.

—Dave (and the rest of Meh)

Cleanse your palate with these sweet Shoddy Goods stories: