Morph for your money: Shoddy Goods 050

The video tech that wowed and worried the '90s

If you're reading Shoddy Goods, the newsletter from Meh about consumer culture, you already look at advertising with an extremely skeptical eye. So it's striking to look back at now-obvious techniques of trickery and realize that people were really worried about their power to deceive. I'm Jason Toon and this week, I discovered you don't even have to go back very far…

In an age of rapid technological advancement, the increasing sophistication of digitally altered video is raising questions about what we can believe and who controls reality. "You can take archival images and enhance," one expert tells the New York Times. "In the wrong hands it could be quite manipulative."

Another expert agrees, raising the alarm about artificial video that is "indistinguishable from reality," in the same article. "Sophisticated people will always suspect from now on. It won't be taken for granted anymore."

This probably isn't the first time you've heard these thoughts this week. But they're not taken from the current cultural debate about AI. They're quotes from 1992 about early digital video manipulation techniques, the buzziest of which was morphing.

An Exxon commercial puts the tiger in your tank into a tiger

"People are not going to do this on their Macs at home"

Computer graphics had been developing for a while, and analog techniques had been used for a morphy effect in movies like The Golden Child. But the first look audiences got at true digital morphing came thanks to - no surprise - Industrial Light and Magic.

While working on Ron Howard's 1988 movie Willow, Doug Smythe of ILM faced the problem of convincingly rendering the animal transformations of the shape-shifting sorceress Queen Bavmorda. He remembered a short film he'd seen a few years earlier by a student named Tom Brigham. That project had used algorithms written by Brigham to smoothly transform an image of a woman into a lynx.

Smythe tracked Brigham down and got to work. The best computers available at the time couldn't quite go from, say, a goat to an ostrich without showing visibly stretched pixels. So Smythe actually built physical models for some of the in-between keyframes. The eventual result was the most realistic shape-shifting ever shown on screen up to that time.

Arise, Goatstrich!

Which is to say, through today's eyes, not very realistic. But it was a big step forward, and it was new and fresh. Morphomania was on.

First morphing was the exclusive province of big-budget blockbusters like Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade, The Abyss, and Terminator 2: Judgment Day. But it wasn't long before it moved beyond sci-fi and fantasy movies to show up in seemingly every commercial and music video. "This could be one of the last books to list all the movies that use morphing," wrote Scott Anderson in the 1993 book - yes, a physical paper book - Morphing Magic. "Soon the list will be too long to print."

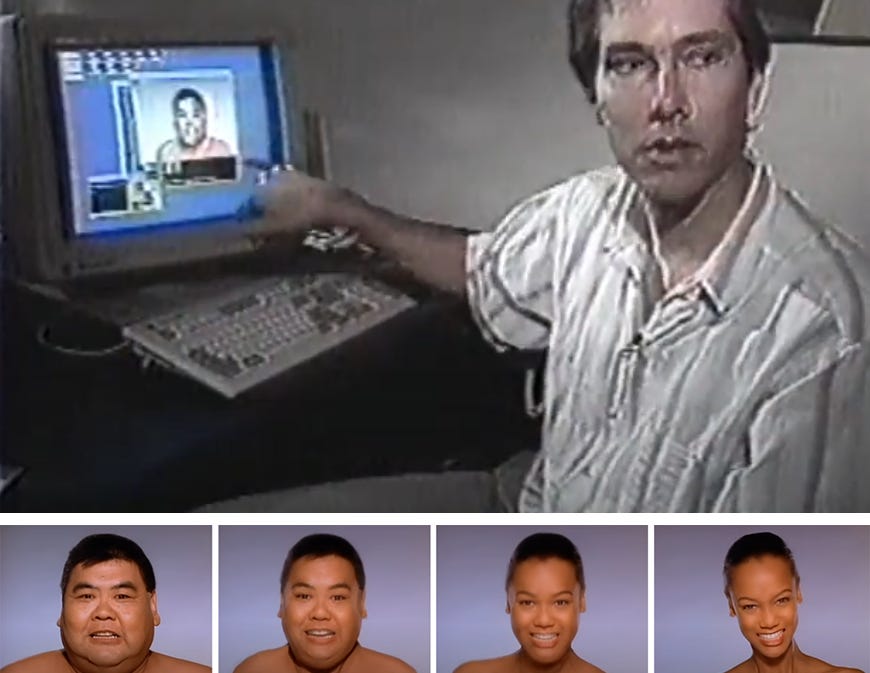

Peak morph was the 11-minute "short film" for Michael Jackson's "Black or White". Everybody remembers the sequence of close-ups on frolicking dancers of different ages, builds, and races that reinforced the song's theme. Less well-remembered is the gratuitous ending where MJ turns into a panther for some reason. Both were incredibly involved to produce, including a video shoot of Jackson and a real panther on an LA street at 2 AM. "Here we were telling Michael Jackson to get on his knees and crawl through puddles," animator Barbara Meier told a newspaper reporter. "It was a strange feeling."

Made with less computing power than your first smartphone

A Prime Time Live report showed the "Black or White" animators moving individual eyelashes to make the morphs look real. Citing the months of work from a team of highly-paid professionals on state-of-the-art equipment to execute less than two minutes of morph video, Meier said "People are not going to be doing this on their Macs at home for a long time. It's complicated."

"Special effects commandos"

Most of the reaction to morphing at the time was of the uncritical gee-whiz variety. "What makes morphing so amazing is that you can watch one image melt into another without being able to describe how it happened, even though you saw every step of the change," wrote computer columnist Craig Crossman in a typical 1992 piece. "The transformations are seamlessly smooth."

Advertisers were all for it. "At last, the cause of creativity in advertising has something to cheer about," wrote Ad Age in a 1991 editorial. "Computer graphics-aided special effects commandos are now providing agencies and advertisers with eye-popping visuals." A Chrysler press release crowed about a commercial campaign featuring Lee Iacocca and some morphing sedans: "The 'Morphing' technique really illustrates just how dramatic a change we have made in our car designs."

But the magic of morphing set off rumbles of unease like those at the top of this piece. Video producer Robert Greenberg, who gave the quote about how archival images could be manipulated, showed a client "how we could take Dukakis and make him as tall as Bill Bradley. We also made Bush look drunk. That's all possible." The same New York Times story related morphing to then-current debates about Oliver Stone's use of faked historical-ish footage in JFK. In 1994, a political commercial in Hawaii was pulled, then reinstated amid controversy about its use of morphing to turn candidates into other, less popular local figures.

What do you get when you cross a Becky with a Becky?

But what really killed morphing was more prosaic: it got old and uncool. By the end of the 1990s, it seemed as dated as Magic Eye posters and wearing bib overalls with one strap undone. And as morphing got easier and cheaper to do technically, humans took less care to get it right, steering morphs into an off-putting uncanny valley. Watch Roseanne's season 8 morph opening and notice how much crappier it is than "Black or White". Fortunately for us fans, the show adopting that opening coincided neatly with it jumping the shark: we know to avoid any episode that starts with a morph (especially season 9's family photo version).

The last laugh?

Nobody back then could have known that the real deceptive potential of morphing lies in those in-between frames. In photo morphing scams, a criminal takes your ID photo and morphs it just enough with their own to be able to pass face ID checks as you. (Uh-oh - did I just enable one Becky to steal the identity of the other?)

More to the point, if we can see the obvious unreality in morphs that people back then swore looked real, are today's concerns about AI video likewise overblown? It's true that, historically, media literacy has more or less kept pace with technology. Maybe after this brief transitional period, the general public will learn to distinguish digital fakes as effortlessly as we can tell that car didn't really turn into a tiger.

This time might be different, though. There's nothing stopping digital video from surpassing the human eye's ability to pick up any red flags of unreality, if it hasn't already. But quality isn't the only difference.

People "doing this on their Macs at home" is old news. All you need is a phone and it's only getting easier. And there's no gatekeeper like a TV station manager or news editor between you and billions of people. It's approaching effortless for bad actors to make and distribute convincing fakes, even in real time - and, given the diverging pictures of reality encouraged by polarized media bubbles, to reach an audience primed to believe it.

Personally, I don't feel like I have any other choice but to be skeptically optimistic about humanity's bullshit detector. My kids are certainly better at spotting AI video than I am. Maybe someday we'll look back at all this and laugh, too. I hope.

Whoa, that looks like a real Muppet! (From a 1993 newspaper article)

My earliest notice of “morphing” tech might be the (terrible) 80s show Manimal, which I just noticed only ran for 8 episodes over 10 weeks and yet is firmly in my memory. What “morphing” videos from the 80s and 90s do you remember? Let’s hear about ‘em in this week’s Shoddy Goods chat.

—Dave (and the rest of Meh)

These links to past Shoddy Goods stories are real… or are they?: