Encyclopedias are my Rosebud. I'm Jason Toon, this is Shoddy Goods (a newsletter from Meh about the stuff people make, buy, and sell), and my fondest childhood wish was to have a full set of the current World Book or Collier's or Funk & Wagnalls gleaming from the shelf, ready in an instant whenever I wondered what the deal was with anteaters or Argentina or abstract expressionism. And that's just volume A.

Before the Internet, there was no other way to satisfy those bolts of curiosity, no other entree into those rabbitholes. Sure, now I can (and do) indulge in the limitless information available through the device in my pocket. But buying a full set of brand-new encyclopedias remains on my "when I win the lottery" list. That's when I'll know I've made it.

But I better get a move on, because there is exactly one general-interest, multi-volume print encyclopedia still being published in English. Only the venerable World Book Encyclopedia is hanging in there, issuing a new print edition every year. I talked to World Book Vice-President of Editorial Tom Evans about what it's like to be the last encyclopedia alive.

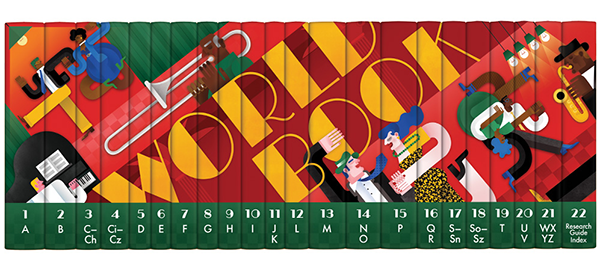

The spine art for the 2025 World Book, commemorating 100 years since the height of the Jazz Age. I'm not drooling, YOU'RE drooling.

Shoddy Goods: I'll start with a question that you probably get all the time, which is what role does a print encyclopedia have to play in the Internet age?

Tom Evans: Sure. I do get that a lot. The first thing is usually "oh, wow, there is still a print encyclopedia", which there still is. And the reason we still produce one is that there's still a demand. World Book was founded as an encyclopedia company, that first one was printed in 1917. Since then, obviously, the business has changed a lot. The main focus of the company now is on our digital line of products, which are mainly subscription-based products for schools and libraries.

I hate to make the Wikipedia comparison, because we're so different, but all the things that are wrong with Wikipedia - sometimes the articles are very hard to understand, they're not written at a level that's appropriate for younger kids, and the information is questionable, because so many people can obviously edit it - that's World Book's strength, and that's why educators have loved World Book for so long.

We work with a lot of experts to make sure that their content is up to date, make sure it's relevant, we're adding new articles constantly. So we maintain digital databases as the main part of our business. Really what happens is the content from that flows into the print set. We still print in the thousands every year because there's a demand. It's mainly public libraries [but] I have to say we get a reasonable amount of orders from individuals who want a set at home. There are a lot of people I still think like that kind of tactile approach: you can grab a volume off the shelf and just randomly learn about something.

Shoddy Goods: So when you're doing the print edition, you're in this unusual position these days. Even though you've got thousands of pages to work with, there's still a limit, unlike a digital thing, which can be theoretically infinite. When you're doing the annual revision, how do you decide what to add?

Tom Evans: Yeah, so there's a few ways that we come to those decisions. One is internally with the editorial team, 22 folks, they're all subject area specialists, they know their area very well, they kind of live in it. So they're keeping the pulse on what is relevant, what is not relevant. They make suggestions themselves. And then they work very closely with our contributors. We have around 6,000 contributors on the books who are often scholars, professors from universities, we've got folks at NASA, Nobel Prize winners, we've got all sorts of folks who are contributing to the content. They make suggestions as well.

But then the other way is indirectly through customers. Because the digital side of our business is so important to us, we track what people are searching for. If we've got students that are looking for some K-pop band or whatever it may be, we know that. And then we react very quickly. We create the content, we maybe work with a contributor, but we get the article there and we post it. We also try and anticipate what a trend may be. So if we see that there's lots of searches for different types of sharks, we want to then expand that area. That then filters into print.

And then the direct customer input is because I get a lot of people reaching out to me and I love it. I get a lot of emails, phone calls, letters from people making suggestions. "Why don't we have this? I think you should have that." And, you know, we look at all those, we respond as we can. I actually got one just a couple of years ago about Ada Lovelace. She was a student, probably 10 or 11 years old. And she said she was studying Ada Lovelace or doing a project, and she was shocked that she didn't have an article in the encyclopedia. And I have to say, so was I, a little bit. So we did put one in. That's more of a rarity, that happens for online more than print, but I love interacting with our customers and I'm glad we have.

Shoddy Goods: And almost more interestingly to me, how do you decide what articles to retire or shorten?

Tom Evans: We use the data again. You know, if we're putting in Ada Lovelace, we'll look for other articles in that area. We're gonna try and stick that within the L volume. Something is coming out. It's a lot of often, like, British lawmakers from long ago. Because these are articles that will probably stem from one of these very early encyclopedias were very relevant at the time and perhaps not so much now. But that's always a hard decision to make, of course.

Shoddy Goods: So in recent years, the concept of objective facts, the very idea that there's a body of fact that we all agree is true, has sort of come under attack, obviously with so much internet misinformation. You're publishing this thing that will probably sit in a library for years. Do you ever feel like you have a responsibility to sort of take a stand for facts?

Tom Evans: I think we take seriously our role. One way or another, we're educators and we take kind of the role of social responsibility very seriously. But in doing that, you know, our role is to provide exactly what you say, the facts. We're not going to provide opinion. And it is harder and harder, because obviously, we have to source information. Even when we work with contributors who are professionals, and eminent in their field, they often going to still have an opinion. So it is hard to do. But that is a struggle we persevere with, because it's really important that we are kind of right down the middle, we're just providing the facts, we're not providing commentary or opinion.

We don't not publish sensitive or controversial articles. We don't skip it. We do it. That's important that we have those articles, but we just present the facts and often will present both sides of something. No commentary: one party thinks this, one party thinks that. But saying that, you know, we have to make some decisions. We're not going to put in the article about Earth that some people think the Earth is flat, because that gives validity to something that's not true.

Shoddy Goods: This is actually weirdly a follow-on from the last question, even though I didn't mean it this way. I noticed in your company history that World Book sponsored searches for the Yeti with Sir Edmund Hillary in 1961, and the Loch Ness Monster with this one-man submarine in 1969.

Tom Evans: That's right. That is true.

"Make room in the 'L' volume, boys."

Shoddy Goods: Do you have any more cryptozoology ventures brewing, or do you think that's probably in the past?

Tom Evans: We don't. One of my editors actually recently visited the museum at Loch Ness in Scotland, and they've still got the submarine with World Book Encyclopedia on the side, it's still in the museum. But you know, going back to certainly the early part of World Book, there was scientific legitimacy in some of those expeditions. By the '50s, '60s, on the marketing side, they played up the Yeti thing because that's what people are interested in. But there was a scientific purpose.

When they went searching for the Yeti, they took all sorts of other scientific equipment because they were researching other things, including how altitude affected breathing in humans. And what I actually love particularly about that story as well, they built a school in Nepal which is still thriving. It was part of the funding for the trip. You couldn't just go there to search for the Yeti. There was a scientific purpose, and then also there needed to be a social purpose.

Shoddy Goods: One more question, just about you personally. You basically have a one-of-a-kind job. What sorts of reactions do you get when you tell people what you do for a living?

Tom Evans: Well, you know, it's funny because the encyclopedia, even though it's still almost a flagship for the company, because it's what people know, it's a very small part of what we do. Of course, when you say World Book, people say, "oh, the encyclopedia, oh, you're still going. You still have one." So I always have that conversation. But really, my job is to provide information and content to students. And so it's perhaps not as unique. The reaction isn't as wowed after we get over the surprise. Teachers and educators and librarians want accurate content. That's all.

I’ll admit, I didn’t even think there was even one print encyclopedia still around, but now I find myself clearing a little shelf space as I justify why I definitely need it. Did you have an encyclopedia when growing up? Any particular entries stand out in your memories? Let us know in this week’s Shoddy Goods chat!

—Dave (and the rest of Meh)

Maybe someday, finer libraries everywhere will carry a print Shoddy Goods Encyclopedia, with articles like these: