The zither craze: Shoddy Goods 075

An exotic instrument strikes a chord in '50s America

When I consider that there are hundreds, even thousands of musical instruments I’ve never heard of, it seems almost arbitrary which ones are familiar to us today. I’m Jason Toon and in this Shoddy Goods, the newsletter from Meh about consumer culture, I look at a moment when one of those obscure instruments broke through to the mainstream.

They knew how to party in 1950

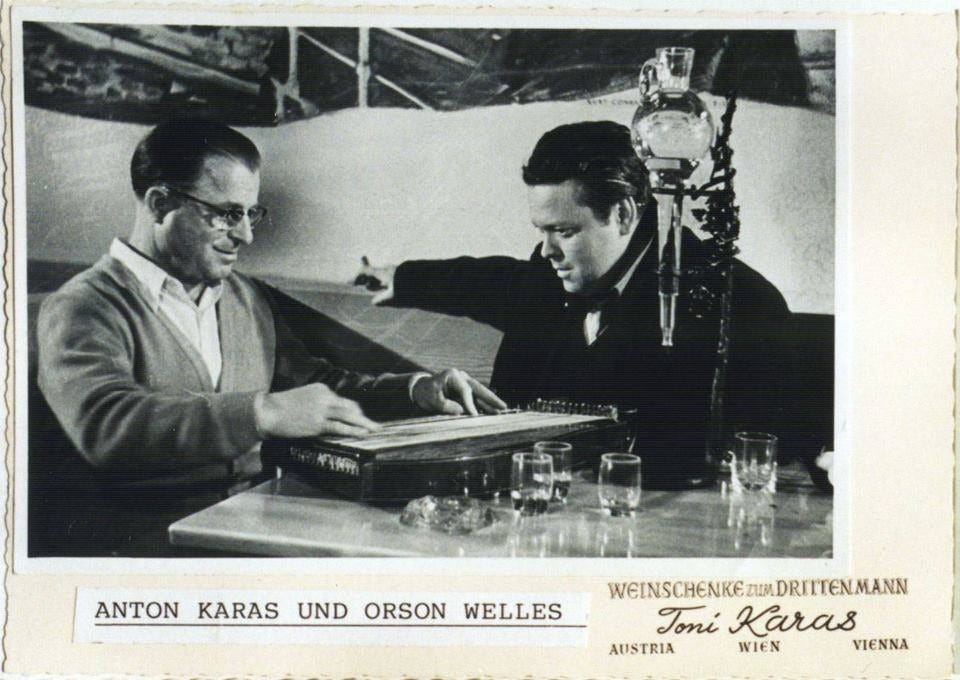

In the rubble of post-World War II Vienna, Carol Reed heard something he liked. The English film director came to town in 1948 to shoot The Third Man, a haunting tale of intrigue starring Orson Welles and Joseph Cotten, and written by Graham Greene. When he stopped in to a wine bar one night, Reed was captivated not by the drinks but by the music.

Simple but rich, refined but gritty, and just exotic enough, it was played on a stringed instrument called the zither by a journeyman Viennese musician named Anton Karas. Reed thought the sound would be perfect for his movie. So, with translation help from bystanders, he asked Karas on the spot to come back to England with him and compose the film’s score. Karas tried to beg off, saying he’d never written music before. But Reed wouldn’t take no for an answer.

The infectious tune Karas came up with - known as “The Harry Lime Theme” or “The Third Man Theme” - was one the biggest and most unlikely global hits of 1950. In the US, it spent 11 weeks at the top of the Billboard chart and was the 3rd-best-selling single of the year, just ahead of a competing version by bandleader Guy Lombardo. The bouncy little Middle European melody would propel both Karas and his instrument into the glare of the spotlight - a place neither of them were quite ready for.

Meet the zither

34 strings and the truth. Watch Anton Karas play the zither

“Zither“ refers to a whole family of stringed instruments where the strings don’t extend beyond the sound box. They don’t have necks, like guitars or violins. The strings aren’t stretched across an open frame, like harps. The family ranges from the Chinese guqin to the Appalachian autoharp to the West African adjulin. Think an acoustic guitar body without a neck, that you play on a table or your lap, and you’re in the ballpark.

Karas specifically played a concert zither, with 5 melody strings on a fretboard (meaning each can play different notes depending on where it’s held down on the fretboard) and 29 accompaniment strings played open (so each can only play the one note it’s tuned to).

The concert zither isn’t some improvised jug-band contraption. It’s as highly refined as any other instrument in the European musical tradition. Watch Karas playing it and it’s obvious the zither isn’t something where you can just pick it up and bang out a little tune. The sound hole gives the instrument its volume and resonance, and Karas’s special low tuning gives it its grit, but the fullness of the sound - hard to believe as one instrument - is all Karas.

We are Viennese if you please

Which is all well and good - but how do you get from that to a pop hit? Ahead of the movie’s release, MGM hired a maverick promo man named Jim Moran to travel around the country posing as a speculator buying up all the nation’s zithers. Moran would inform the local media that he’d pay $50 (about $650 today) for any used zither, before The Third Man made zithers a hot commodity. “I’ll be rich,” he told the Galveston Daily News, while insisting his quest had nothing to do with promoting the film.

More likely, the tune’s inherent catchiness and freshness was enough to prick up American ears. Contrary to the stereotype of the staid whitebread ‘50s, a series of imported musical styles enjoyed brief vogues through the decade, from rumba and calypso to bossa nova and Irish folk. “The Harry Lime Theme” scratched that exotica itch first, and the zither craze was on.

“Out of a basement”

The door was open for a wave of zither-pop that would last a decade. Ruth Welcome‘s romantic solo zithering got her signed to Capitol Records, while Australia’s singing zitherer Shirley Abicair moved to London and became a bona fide star well into the ‘70s.

Who’s ready to get zithered?

At the grassroots level, the aging members of zither clubs from Buffalo to Honolulu found themselves unexpectedly aligned with the mainstream. Mostly Germanic immigrants and remnants of an early zither craze during the 1880s, these last zither diehards anticipated new blood. When a Portland, Oregon newspaper said the zither was dead, a dozen local players protested. “I have much hope,” said Adolph Robl, former president of the Zither Club of Baltimore, told the Baltimore Sun in 1950.

There was just one problem: it was hard to find zithers. The only zither factory in America at the time was a one-man operation run by Albert Hesse of Washington, Missouri, who hilariously couldn’t have cared less about cashing in on the new fad.

The St. Louis Globe-Democrat reported the 73-year-old craftsman was content to “putter about the plant a few hours each day”, repairing old zithers and filling orders for strings, paying no attention to the 10-20 mail requests from the newly zither-curious. “If I did, I’d never get any work done.” He closed down for good in 1954.

What did Hesse think about Karas’s breakthrough hit? “I did not hear it,” he told the Chicago Tribune. “I guess they got the player out of a basement or a beer stube.”

That’s the kind of talk that could start serious beef, except Karas had started to hate his signature tune, too. “This tune takes a lot out of your fingers,” he said. “I prefer playing ‘Wien, Wien’, the sort of thing one can play all night while eating sausages at the same time.”

He was in demand as a touring act overseas, which he also hated. “It is because of that film that I was pushed from one place to the other,” Karas said. “My only desire was to be back home again.”

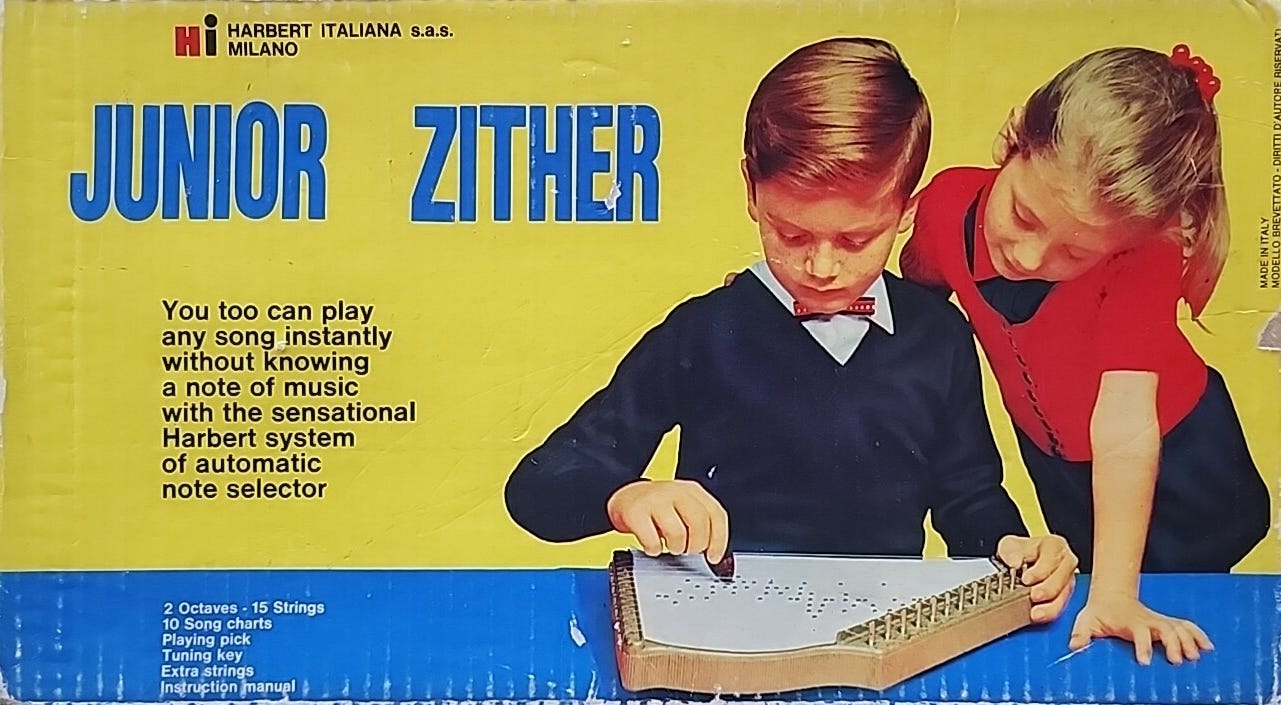

So, with real instruments limited to pricy imports or dusty 70-year-old castoffs, and a reluctant star who’d rather stay home and eat sausages, the ‘50s zither craze did not spawn a boom of new zither players. But, doubtless to the irritation of those stern Teutonic zither perfectionists, it did spawn the Junior Zither.

Bowtie required

Essentially a music-education toy, the Junior Zither came with song sheets you could slide under the strings that showed you exactly how to pick out simple melodies on the order of “Twinkle, Twinkle, Little Star”. It’s a long way from the virtuosity of Karas. But the idea must have resonated (sorry), because variations like The Music Maker Lap Harp remain on the market today - I can’t resist plinking around on it whenever I see one at a toy store.

While “The Harry Lime Theme” still sounds strikingly original today, the brief ‘50s zither fad is now as long ago as the 1880s craze was then. Maybe that means it’s all firmly consigned to history’s attic - or maybe we’re due for another zither craze.

I never got pushed to try any musical instrument out as a kid. I suppose I enjoyed not having my afternoons forced into relentlessly practicing scales, but I do feel like I missed out a little on not being able to hammer out Christmas tunes on call.

How about you? Ever learn, or attempt to learn an instrument? If you could, Matrix-style, instantly be an expert at one, which would you pick? Let’s discuss in this week’s Shoddy Goods chat.

—Dave (and the rest of Meh)

Have you heard? Everybody but EVERYbody is talking about these fresh, original Shoddy Goods stories: