Dictabelt was there: Shoddy Goods 078

Capturing history with the Forrest Gump of office supplies

Happy New Year! Jason Toon here with another Shoddy Goods, the newsletter from Meh about consumer culture. This week we look at a mainstay of the midcentury office that had a knack for winding up in the darnedest places…

As soon as people could record sound, we started using it to dictate business communication. The company that became Dictaphone was founded in 1881 by a guy you may have heard of named Alexander Graham Bell. For decades, dictation was saved to wax cylinders and lacquer discs; later it moved on to magnetic tape and today’s digital voice memos. But for a time in between, from about 1950 to 1980, the most popular dictation medium was a flexible loop of thermoplastic called the Dictabelt.

As befit its workaday purpose, the Dictabelt was meant to be ephemeral, a temporary stop between a business executive’s mind and a typist’s hands on its way to paper, where real business was done. So when it turned out that this cheap and literally flimsy recording medium captured some of the most important historical events of its time, only some heroic restoration efforts kept those sounds from fading away.

“Link between minds”

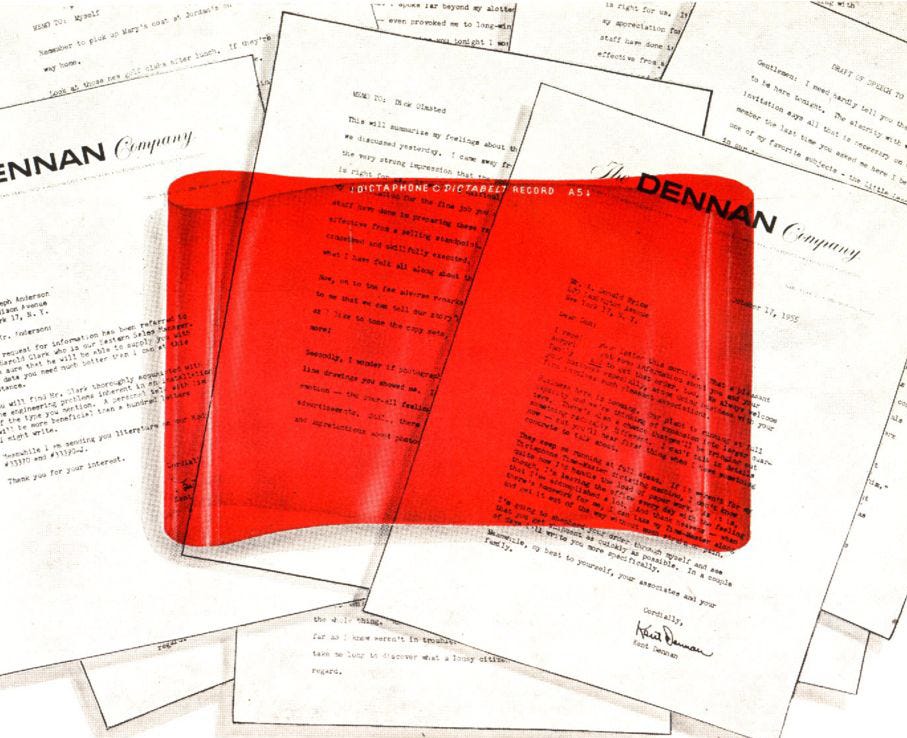

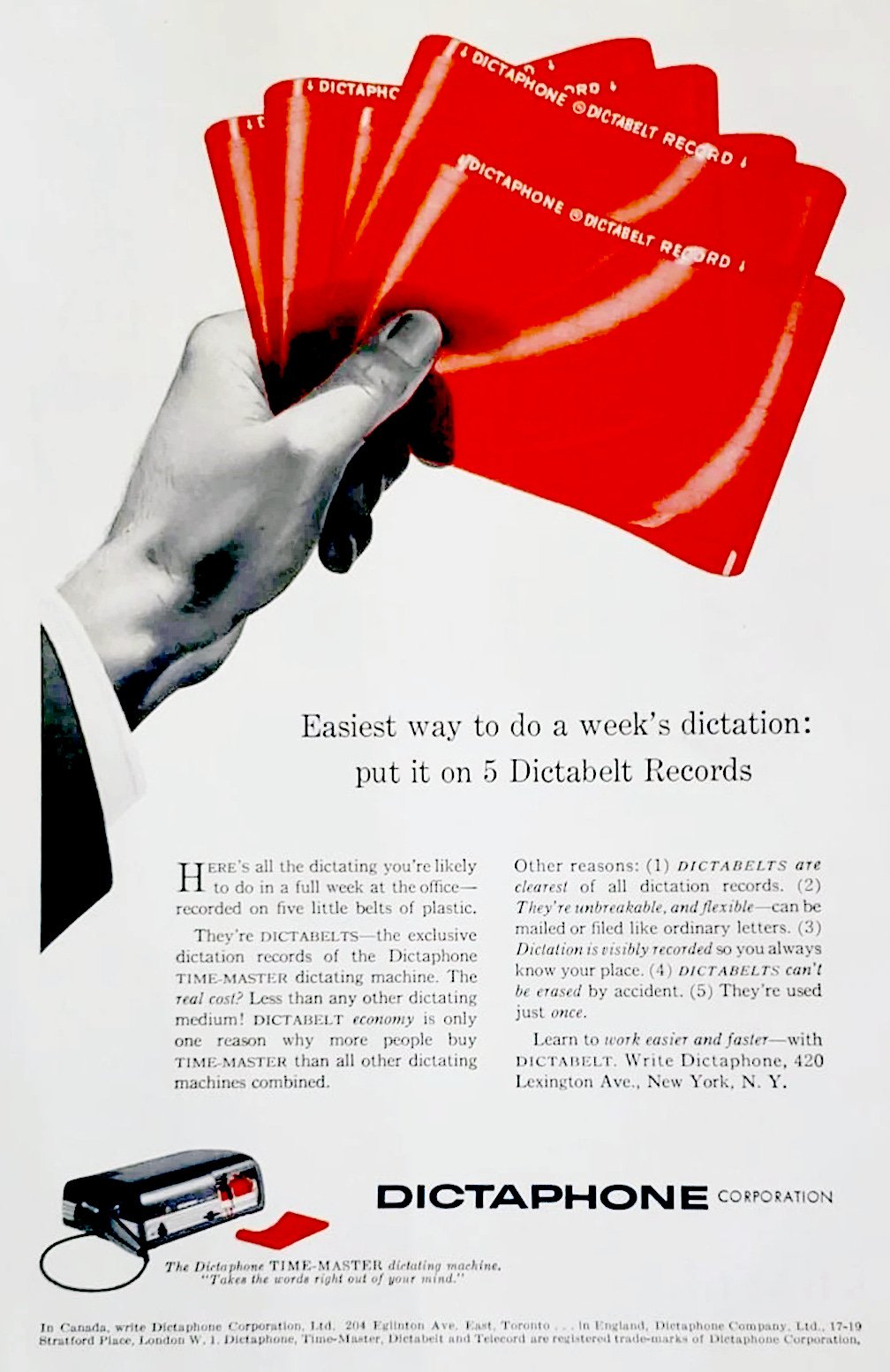

“They’re unbreakable, nonerasable, feather-light.” So ran the copy for the Dictaphone Dictabelt in a 1956 print ad campaign. The contrast with bulky, brittle, awkward cylinders and discs is as clear as the Dictabelt itself. Here was a new, streamlined, brightly colored medium suitable for the go-getters of the Jet Age: “a simple, fast, efficient link between minds,” as another ad put it.

Dictaphone’s wax-cylinder recorders had been so successful it was starting to feel the Kool-Aid/Kleenex effect of becoming a genericized synonym for dictation machines. But in the years after World War II, the company suddenly found itself facing stiff competition from new recorders that cut plastic discs, like the SoundScriber and the Edison Voicewriter. So a lightbulb went off for the smart people at Dictaphone HQ.

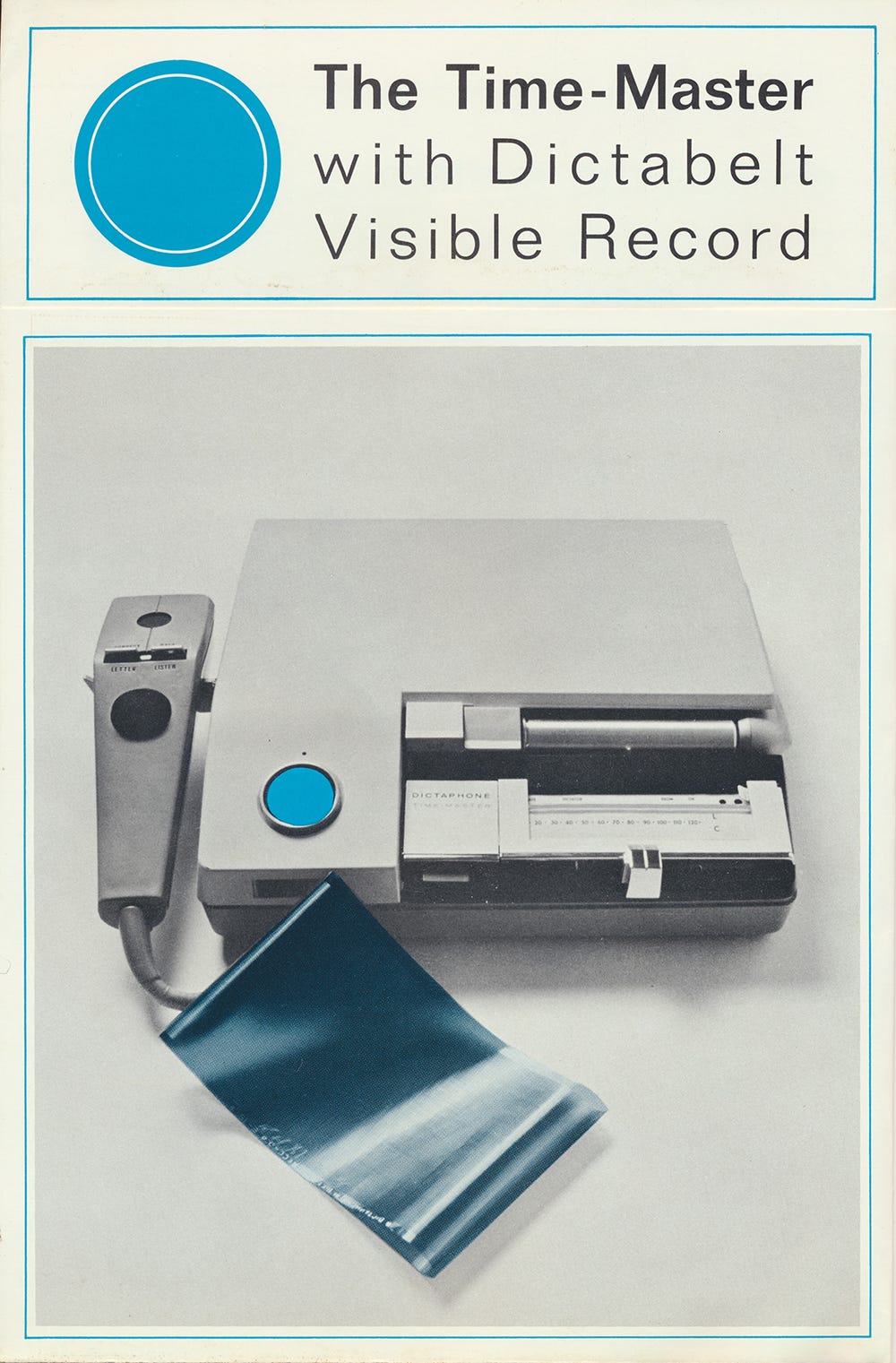

Taking advantage of advances in plastics, Dictaphone released the new Time-Master recorder in 1947, with a blunt stylus that impressed a playable groove into a flexible loop of colorful plastic. About 3.5 inches across and 12 inches in diameter, each loop - first called the Memobelt, then the Dictabelt - could hold 15 minutes of hi-fi recording or 30 minutes at slower, lower fidelity.

Once again, Dictaphone had read its audience correctly. Within a few years, the Dictabelt became standard in offices and government agencies across the US and UK, and increasingly around the world.

From Twilight Zone to grassy knoll

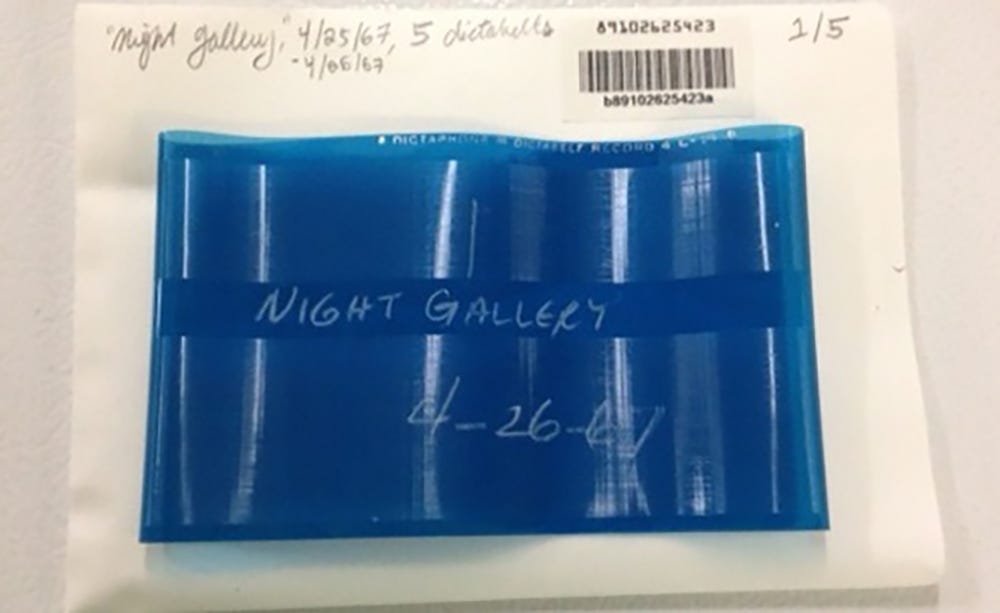

The Dictaphone Time-Master, with its lightweight Dictabelts, was cutting-edge technology at the time, and society’s movers and shakers took notice. My personal hero Rod Serling left behind over 1,100 Dictabelts of him dictating his screenplays for The Twilight Zone and Night Gallery. Bing Crosby was a prolific Dictabelter, with private recordings from his archives forming the core of a 2014 PBS American Masters documentary.

In an even higher echelon, at least four US Presidents - Eisenhower, Kennedy, Lyndon Johnson, and Nixon - used them not just for voice memos, but to secretly record Oval Office conversations. From mundane office chit-chat to key decisions around Vietnam and Watergate, it’s all there. Remember all those blockbuster revelations of unearthed presidential “tapes” that kept hitting the news back in the late ‘90s and early 2000s? They were usually talking about Dictabelts.

The best-known, most closely studied Dictabelt of all time also has a presidential connection, albeit a tragic one: a 5.5-minute Dictabelt recording of Dallas police radio traffic from the morning of John F. Kennedy’s assassination.

Some have interpreted gunshot-like sounds on the recording as evidence of a second shooter, with a different gun, in a different location than Lee Harvey Oswald. In 1978, the House Select Committee on Assassinations thought enough of the evidence to conclude there was a “high probability” of multiple shooters. But of course, other, equally credentialed analysts have reached contrary conclusions. It’s far beyond me to litigate the claims; if you want to fall down that rabbit hole, it’s easy to find elsewhere. The point is, the Dictabelt went places that Dictaphone couldn’t have imagined.

“The ideal of a free society”

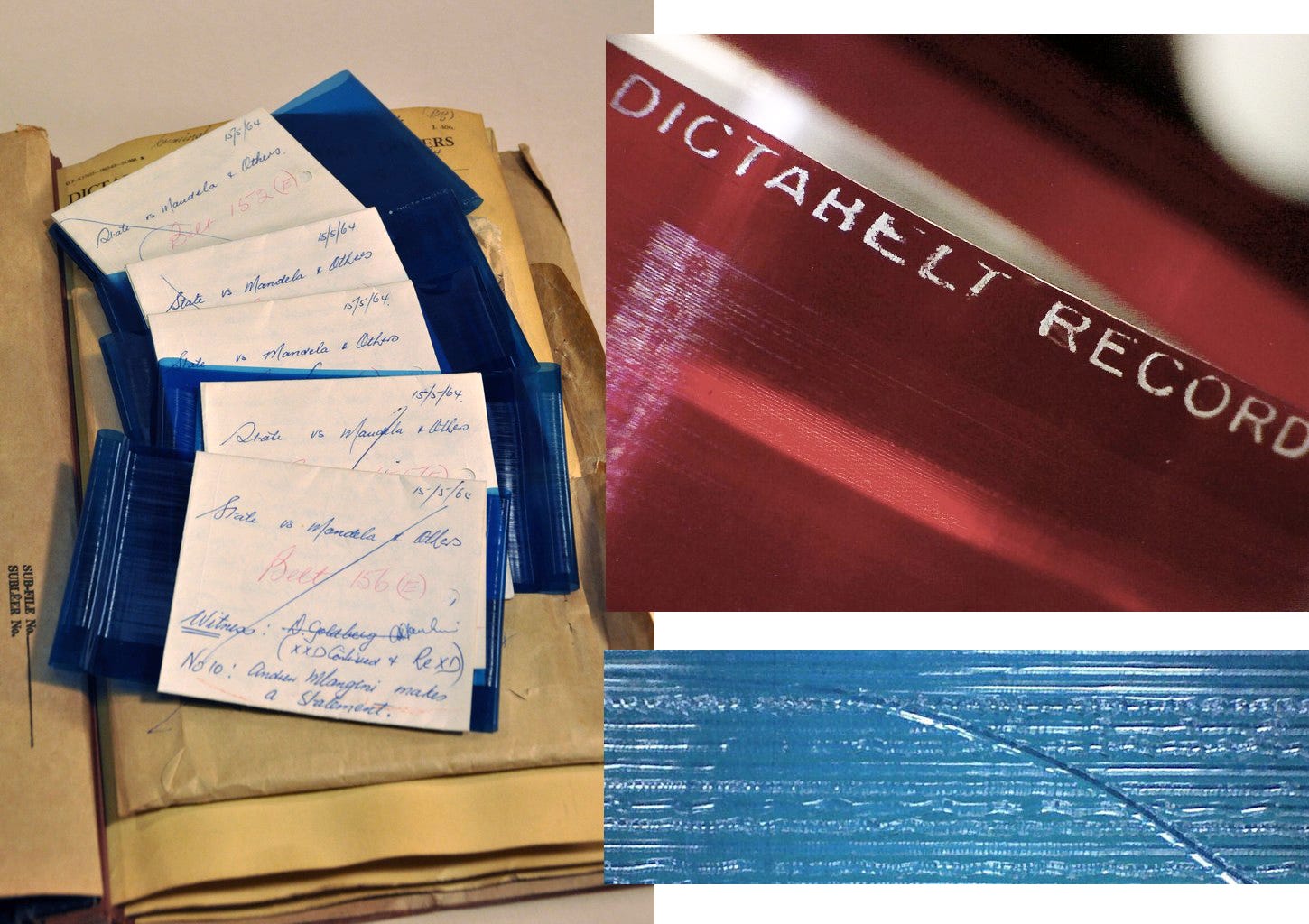

In 1994, another trove of historic Dictabelts emerged from an unlikely place: post-apartheid South Africa. In the 1964 “Rivonia trial” that sent him to prison, Nelson Mandela had delivered a three-hour opening argument whose final words had become a famous rallying cry: “I have cherished the ideal of a democratic and free society in which all persons live together in harmony and with equal opportunities. It is an ideal which I hope to live for and to achieve. But if needs be, it is an ideal for which I am prepared to die.”

The trial had been recorded on a Dictaphone Time-Master, with the Dictabelts then filed away by the apartheid government. When that regime finally fell, and Mandela was freed, the archives were opened to reveal some 591 rapidly decaying Dictabelts, some red, some blue. Equipment to play them on was hard to come by, let alone to restore the brittle, creased vinyl loops to playable condition.

The seven on which Mandela spoke were digitized in 2001 with help from the British Library and an unusual additional appliance. “To avoid the Dictabelts splitting and to flatten out the creases which had set over the years, the whole machine, with its Dictabelt, needed to be operated at an elevated temperature,” writes Liz Tuddenham. “The heat was provided by standing the Dictaphone on an industrial hotplate.” Look, it was 2001, they did their best.

The remaining Rivonia trial Dictabelts weren’t digitized until 2016-2017 by audio restoration expert Henri Chamoux of the French Institut national de l’audiovisuel, who had a few choice words for his British predecessors and their hotplate: “two of these seven dictabelts, perhaps due to these manipulations, are damaged: they bear severe scratches not found in the rest of the collection.”

Cross-Channel rivalry aside, Chamoux used his own invention, the Archeophone, to play the belts on a cylinder instead of across two rollers. He was able to adjust the diameter of the cylinder to subtly increase the tension on the belt and smooth out the creases during playback. Sometimes, for a particularly rough patch, he’d play the belt backward, then digitally reverse it. Chamoux estimates it took him 1600 hours to digitize the 256 hours of Dictabelts from the Rivonia trial - basically, a year of full-time work.

For whom the belt tolls

If it takes that much effort to restore recordings from a key event in the history of a nation, imagine all the other interesting Dictabelt audio currently rotting away around the world, never to be restored.

The rise of magnetic tape, first on reels then on cassettes, spelled doom for the Dictabelt. They declined through the ‘70s until they were finally discontinued in 1980. Nobody cared much about preserving those now-useless Dictaphone Time Master machines, so even the Dictabelts that were saved weren’t playable on anything.

But maybe the bright spot is that those Dictabelts that have been digitized are now safer from not just physical decay but the ebb and flow of proprietary, device-specific formats. This is why I’m thankful that the old idea of a decentralized, open Internet is still hanging on despite the monopolies gobbling up so much of it, and thankful for the efforts of a million anonymous archival obsessives who make this newsletter possible. Which reminds me, it’s a good time to make my little annual donation to archive.org.

Do you have any recordings from back when you were a kid? I’ve got an old cassette tape labeled “mom and son reading poems for Idelia” that I need to find a way to get a digital copy of, but that’s about it. I can’t imagine what it’ll be like for kids these days who have hundreds of hours documenting their childhood. Let’s talk about it in this week’s Shoddy Goods chat.

—Dave (and the rest of Meh)

These past Shoddy Goods stories are even more flexible and lightweight, and sure to win the Baxter account: